Article produced by Michael Mainelli, Chairman, Z/Yen Group & Simon Mills, Senior Analyst, Z/Yen Group.

Z/Yen Group is a partner of Farnborough International Space Show.

Space Debris – Market Mechanisms and the Tragedy of the Commons

Introduction

Space, in particular the satellites in low-Earth orbit, is a crucial component of 21st century society. From providing access to the internet for remote and war-torn corners of the globe to providing real time data to insurers and farmers on weather patterns, space-based technologies have an essential role to play in providing the data that make markets function.

However, as the competition to provide space-based services hots up, orbits are becoming crowded, and a new menace is raising concerns – that of space junk.

The Space Race

The last two decades has seen a rapid expansion of commercial activity, particularly with respect to launch capability, which has seen the cost per kilo for payload launches drop from over $100,000 per kilo to under £2,000. At the same time, advances in technologies such as robotics, remote sensing, and artificial intelligence have catalysed opportunities in digital mapping, enhanced communications, navigation, and resource and environmental management – particularly with respect to biodiversity and carbon emissions.

Crowded Orbits

There is no international body responsible for regulating who launches what into space, instead oversight is maintained by a patchwork of over 30 national regulatory frameworks. Today the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) keeps a register of objects launched into orbit and maintains a watchful eye on the exploration and use of outer space under the Outer Space Treaty. [1]

Article IX of the Outer Space Treaty specifically states that “Parties to the Treaty shall pursue studies of outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, and conduct exploration of them so as to avoid their harmful contamination”.

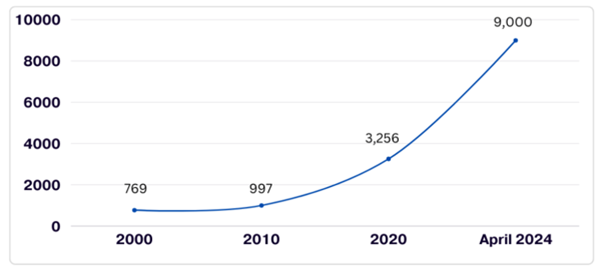

The number of active satellites in orbit, as of April 2024, reached over 9,000 and some reports suggest that by 2030, we could have more than 60,000 active satellites in space [2], boosted both by Starlink (which, as of January 2025 has 6,912 satellites in orbit) and China’s Gesi Aerospace Technology, also known as Genesat who are planning a mega-constellation of 13,000 satellites.

Figure 1: Active Satellites In Orbit

Source UK Government 2024

Each launch can propel multiple satellites into orbit which weigh between 1 kilogramme and 15 tonnes. Space is a very unforgiving environment, and satellites face particular peril at the launch phase, when vehicular failure can destroy many millions of euros of equipment (2023 was a particularly torrid year for space insurance with losses running at over $1bn dollars). [3] Even if the launch is successful, the successful deployment of the satellite in the correct orbit is a major technical challenge.

Space Junk

Space debris, also known as space junk, refers to the collection of defunct human-made objects in Earth’s orbit. These objects range from dead satellites and spent rocket stages to smaller fragments resulting from explosions, collisions, or disintegration.

Scientists estimate the total number of space debris objects in orbit to be around 29,000 for sizes larger than 10 cm, 670,000 larger than 1 cm, and more than 170 million larger than 1 mm. About 65% of the catalogued objects originate from break-ups in orbit – more than 240 explosions, caused by uncontrolled hydrazine reactions – as well as collisions [4].

Among the larger objects, there are approximately 2,000 inactive satellites and spent rocket stages. These larger objects are tracked more accurately than smaller fragments.

Figure 2: Composite Image of Space Junk Orbits

Source: European Space Agency [5]

Most ‘space junk’ moves extremely fast (7.8 km/s is low-Earth orbital velocity) and due to the speed and volume of debris in LEO, this present a significant threat to current and future space-based services as LEO is, according to NASA “the world’s largest garbage dump” [6].

Space debris is a rising global risk that needs to be addressed as the accumulation of space debris significant risks to both operational satellites and crewed space missions. Of particular concern is that with thousands of active satellites and an estimated 128 million debris objects larger than 1 mm in orbit, the probability of collisions between space debris and operational satellites is increasing. Each collision creates more debris, setting off a chain reaction known as the Kessler Effect[7], where the density of debris in certain orbits becomes so high that it significantly impairs future space activities.

Despite this risk there are no international laws requiring companies to clean up debris in LEO, although national regulators are beginning to wake up to the risk. On 2 October 2023, the United States Federal Communications Commission (FCC) issued its first ever fine to a company for littering in space [8]. The FCC’s investigation found that the company violated the Communications Act, and the terms of the company’s license by relocating its direct broadcast satellite EchoStar-7 at the satellite’s end-of-mission to a disposal orbit well below the elevation required by the terms of its license. At this lower altitude, it could pose orbital debris concerns. The settlement included an admission of liability from the company and an agreement to adhere to a compliance plan and pay a penalty of $150,000.

Although, the sum is negligible, this is a landmark decision, following on from a 2022 decision to adopt new rules requiring satellite operators in low-Earth orbit to dispose of their satellites within five years of completing their missions, significantly shortening the long-held 25-year guideline for “deorbiting” satellites post-mission.

Unfortunately, it stops short of plans floated to require satellite operators to indemnify the U.S. government against harm caused by their satellites, which could include the introduction of a performance bond (that could reach $100 million for mega constellation operators)[9].

Potential Solutions

There are several interlinked approaches which can be used to tackle the problems of space debris:

- Space Debris Tracking And Monitoring: Enhancing global tracking and monitoring capabilities to catalogue and predict the movements of space debris would provide essential data for collision avoidance manoeuvres and future planning.

- Debris Mitigation Measures: Encouraging satellite operators and manufacturers to adopt best practices for debris mitigation, could include designing satellites with built-in deorbiting capabilities, minimizing the creation of debris during satellite deployments, and implementing end-of-life disposal plans.

- International Collaboration: Fostering international collaboration and cooperation among space agencies, private industry, and regulatory bodies would help to develop and enforce comprehensive space debris mitigation guidelines and standards. Establishing mechanisms for information sharing, joint research, and coordinated efforts would address the global nature of the space debris problem.

- Research And Innovation: Investing in research and development of advanced technologies and materials would help mitigate the risks of space debris. This includes improved shielding technologies for spacecraft, better tracking and monitoring systems, and innovative propulsion methods for satellite deorbiting.

- Public Awareness And Education: Raising public awareness about the challenges posed by space debris and the importance of responsible space operations would help to educate the public, policymakers, and future space professionals about the potential consequences of space debris.

- Active Debris Removal (ADR): Developing and deploy technologies for actively removing larger debris objects from orbit, such as capturing and deorbiting defunct satellites could significantly reduce the risks posed by existing large debris items.

Figure 3: ADR Concept ClearSpace 1

However, the most effective leverage could be applied through the insurance sector.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development points out that: “While not strictly a debris mitigation measure, in-orbit insurance, in particular third-party liability insurance could play an important in shaping operator behaviour and contribute to covering remediation costs”[10].

Despite this, it is estimated that currently only six percent of satellites in low-Earth orbit have in-orbit insurance. A recent paper, published at the International Astronautical Congress in Baku [11], proposed the of performance bonds and P&I mutuals to reduce premiums by spreading exposure.

Performance bonds could be offered for satellite retirement and anti-collision insurance- these are financial instruments that guarantee the funding required for the safe deorbiting or retirement of satellites at the end of their operational life if the satellite does not safely deorbit or retire according to plan.

A requirement to obtain such a bond before getting permission to launch would ensure that satellite operators retire their satellites in a responsible manner and adhere to established guidelines for sustainable space operations.

Fundamentally anti-collision insurance coverage should be mandated by the regulatory bodies responsible for overseeing the space sector in each jurisdiction. This would be taken by satellite operators, space agencies, and commercial space ventures. This insurance would protect against financial losses resulting from collisions with space debris or other operational satellites.

Progress

Financial district known as the City of London is the global centre for insurance and reinsurance, and as such it has a particular interest in addressing the issue of space debris, which is why the 695th Lord Mayor, Professor Michael Mainelli, launched the Lord Mayor’s Space Protection Initiative, with the assistance of Z/Yen the City’s leading think tank, at the International Astronautical Congress in Azerbaijan [12].

Momentum grew rapidly, with an “Invitation to treat” letter from Lloyd’s reinsurance offering up to US$500m per operator backed by six global underwriters. The issue was discussed by the world economic forum at Davos and in June 2024 Professor Manahel Thabet launched the Commonwealth Space Collaboration Initiative “CommonSpace Making Space Work For All ”[13].

This was followed by a World Economic Forum workshop at Mansion House, on Financial Space Debris Mechanisms [14] which fed into the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM), in Samoa and from their it went on to the United Nations General Assembly.

Although the wheels of the international diplomacy grind slowly, it is highly likely that within the next few years international treaties will be amended to address the growing issue of space debris.

Meanwhile the UK, in accordance with the National Space Strategy, is ramping up its efforts

in space sustainability. This includes two Active Debris Removal Phase B mission studies which will help the UK Space Agency to take forward a demonstration of the nation’s capability to rendezvous, dock with, and deorbit two defunct UK satellites in 2026 .

Conclusions

The current situation with respect to space debris and orbital crowding in LEO is “the tragedy of the commons” writ large. Without international cooperation and effective regulation, underpinned by effective insurance products, the possibility of a Kessler Syndrome event occurring within the next decade increases in probability – and the more debris there is in orbit, the higher the insurance premiums and the lower investors’ appetite. To quote one senior practitioner involved in the sector- “Why throw billions into orbit if it has a high risk of getting shredded?”

Action is required to protect space, and the insurance industry and the nascent In-Orbit Servicing industry stand ready to facilitate that action. That action could come in the form of a Debris Attribution/Tracking index, international agreement to leverage insurance for liability and removal of debris for satellite operators. That action will preserve the benefits of space for society today and put it on a sustainable footing for the future.

The satellite insurance market presents unique challenges for insurers, especially with potential high risk of exposure for individual incidents. It is time that operators, insurers, and government come together to consider alternative possibilities to provide effective coverage against the risks inherent in satellite operations, while taking the opportunity to promote best practices across the satellite industry.

We are looking forward to discussing these issues at our specialist panel at the inaugural Farnborough International Space Show (FISS), which will be taking place on 19 & 20 March 2025 at the Farnborough International Exhibition and Conference Centre, United Kingdom.

Bibliography

[2] UK Government 2024 The Future Space Environment

[3] Perkins R 2024 Space Insurance Rates Rocket as major losses and capacity contraction hit

[4] European Space Agency, (retrieved 2023)

[5] European Space Agency (accessed 2023)

[7] ESA (accessed 01 25) The Kessler Effect and how to stop it

[8] FCC 2023 FCC Takes First Space Debris Enforcement Action

[9] Henry C 2023 FCC punts controversial space debris rules for extra study, Space News

[10] OECD 2020 Space Sustainability: The Economics Of Space Debris In Perspective, page 35

[12] Mainelli M et al 2023 In-orbit servicing and insurance markets: a symbiotic approach

[13] The Commonwealth 2024 CommonSpace Making Space Work for All